|

|

|

|

|

|

|

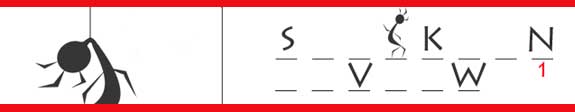

Edith's Summer Edith spent most of her day talking to a cow she had named Albert. Three days after summer vacation started she walked along Spring Creek, being careful where she stepped, as Albert walked along beside her. “This summer will never, ever end,” said Edith. Albert’s sad eyes seemed to understand. “Why do you spend so much time with that cow?” asked her mother. Edith shrugged. “Find something else to do, Edith.” In the morning, as the air was filled with the sounds of the birds and the farm animals starting their day, Edith was silent, sitting on a stool on the back porch, her forehead resting on the railing, her hands drooping at her side, a picture of despair. Next to Edith, her grandmother was sorting green beans, snapping the ends off the good ones. Even though her hands were gnarled up like fists, she was very good at the bean job. “You look busy,” she said to Edith. “I’m not,” said Edith. Then she looked up and sighed a grown-up sigh, a sigh out of all proportion to her small stature. “Grandma, do you think it’s a bad thing that I talk to Albert?” Grandma said she thought it was good for Albert and it probably wasn’t doing Edith any harm, but that, whatever the case, Edith should try to find something else to do, at least until her mother forgot about Albert, which wouldn’t take long. “But, Grandma, there is absolutely nothing to do. It is so boring around here. There’s nobody to play with. Mother and Dad work all the time. Being eight is hard.” “Try being eighty,” said Grandma. “You want to play cards?” “What game?” “You choose.” “I only know one.” Mother thought this was a good idea. Since there was nothing else to do, Edith said okay. Grandma loved to play cards. At first, Edith won almost every game, and she liked to win, then Grandma started winning and they discovered Edith did not like to lose. Edith and Grandma wasted beautiful sunny summer afternoons sitting at the kitchen table where Edith’s mother was trying to cook or iron or sew. Edith and Grandma played cards every day and got in huge fights. “How can they get in fights playing Go Fish?” said Edith’s father. “Do you have any threes?” “Go fish.” “Yes, you do. I just saw you pick one up.” “That’s cheating.” “I wasn’t trying to look. So it’s not cheating.” “Yes, it is.” Mother took the cards away. For a few days Grandma and Edith simmered. They did not talk to each other. Finally, Mother kicked them both out of the house. “Go talk to Albert,” she said. Edith and Grandma took a walk in the meadow and sat down on the bank of Spring Creek among the grazing cows. They pulled the tall grasses, bit the sweet juice from the tip, lay back, and looked up at the clouds. Albert, as usual, was grazing close by, close enough so Edith could hear him biting and chewing the sweet grass himself. When they were in the meadow the three of them were always close together. “What are we going to do about Mother?” said Edith. “She’s driving me crazy.” “I have no idea,” said Grandma. “She hid the cards and won’t tell me where they are.” “You’re her mother, aren’t you? You can tell her what to do. Tell her to leave me alone.” “Sorry. I tried. I did everything I could. But after she turned two she stopped listening to me and started doing just what she wanted to.” “Well, tell me what I should do,” said Edith. “This can’t go on.” “I think the best thing is just let her go her own way.” “She wants to dress me and make me do chores and read books and stuff. I mean I can just barely read. One book would take forever. This morning she said I had to learn how to cook. Can you imagine? I’m only eight.” “Yes, well, she does the same thing to me. She keeps bringing home dresses she wants me to wear. Potato sacks with flowers painted on. I hate flowers. I just ignore her.” “Sheesh,” said Edith. “It’s hopeless.” After a few minutes, Grandma said, “It wouldn’t kill you to learn how to cook.” “Forget it, Grandma.” Lying in the grass beside the lazy creek, looking up at clouds drifting and reshaping themselves, Grandma turned toward Edith, “You know, Edith, that Albert is a girl.” “We’ve been over this before, Grandma. Albert is a boy. You’re just trying to start an argument.” Grandma took the weed from her mouth and tickled Edith’s nose. “Edith, all of the cows are girls. They give milk. Only females give milk. The bulls are boys; the cows are girls.” Not in the mood for Grandma’s silliness, Edith brushed the weed away and rubbed her nose. “Grandma, I have known Albert since he was a calf. I really do not care to discuss it further. He is a boy.” “All right, Edith—if you say so.” Grandma patted Edith’s arm. “I used to think that horses were boys and cows were girls but I learned that I was wrong and now I see that I am apparently wrong again.” Then she drifted off into one of her naps. Edith stood and looked down at her eighty-year-old grandma lying in the grass with a weed between her lips, her interlaced fingers crossed over her chest, which was slowly rising and falling. Edith turned and walked over to Albert. When she was close to him he made soft little noises that meant something. She knew he had been listening when Grandma called him a girl. “Can you believe all that nonsense?” she said softly into his ear. * * * Grandma and Edith went down to the pasture and sat by the creek every day, and that made Edith’s mother happy, but, now that the cards were hidden and the issue of whether or not Albert was a boy was settled and no longer up for discussion, there wasn’t much to argue about, so they just looked up at the sky. Edith did not do her chores and her dad did not push her. He was spoiling her, her mother said, and he agreed. Grandma never mentioned the chores one way or another. When Grandma was napping in the grass, Edith talked to Albert, patted his brown flanks, and smelled his grassy breath. When she was close to him, he made his little noises. He was talking to her and some of it she could understand. Edith walked over to the apple tree next to the stream. Grandma’s eyes were open, looking up. She patted the grass. Edith lay down next to her and looked up. Overhead, a hawk was circling. Crows were cawing in the apple tree. “What are they talking about?” asked Grandma. “Who?” said Edith. “I don’t hear anybody.” “The crows. They’re cawing. What are they cawing about?” “I have no idea,” said Edith. “Well, you and Albert talk. You understand Albert. Why can’t you understand the crows?” asked Grandma. “Because they are talking to each other. Albert talks to me.” “I see,” said Grandma, feeling around for a new stalk of grass without taking her eyes off the hawk. “Really, Grandma, I can understand Albert. Honest.” “I see.” Edith watched the hawk, wings spread, making perfect circles. “But,” said Edith, “fish don’t talk. They just swim around. I watch them. They swim right past each other. They don’t even look at each other. They couldn’t hear each other anyway, not underwater. They don’t have brains. If they did, they wouldn’t get caught.” “Is that your final word on the subject?” said Grandma. “Yes,” said Edith. “And squirrels communicate with their tails and tell each other where the nuts are and bees buzz and—” “Oh, be quiet,” said Grandma. “You’re jabbering like a squirrel. Just listen. Lay still. Open your ears. Close your eyes.” Edith listened to the sounds of the meadow. If she sat really still and opened her ears, she could hear the birds and the animals talking to each other. They all squawked to each other. Then she opened her eyes and she noticed that the rabbits didn’t talk and cows touched each other. * * * The next day, under the apple tree, Edith said, “Here’s what I think. You may be right that Albert doesn’t actually talk, but I can understand Albert, not so much his words, but, I mean, I understand him. I really do. Honest. The noises he makes are part of it, but they may not be actual words. So, what I think is that they do it mostly without words. They do it mostly with touching—with their tails and paws or whatever they have, like wings, for example—and the noises are not really words.” “But not fish,” said Grandma. “No, not fish,” said Edith. “I’m sure about that.” Grandma looked up in the sky and smiled to herself. “Well, well, well,” she said. “If animals can communicate that way, without words, then how come you and I can’t? Aren’t we smarter than a cow? I know I am. But maybe you aren’t.” “Don’t be silly. Of course I am. If you could do it, I could do it.” “Harrumph,” snorted Grandma. Edith jumped up on her knees and leaned over her Grandma, “Of course we could do it too, you and me. This is the best idea you ever had. No talking. I bet we can do it.” “I’m not so sure your mother will approve.” Edith’s face was an inch away from her Grandmother’s nose. “Who cares?” Grandma was smiling and shaking her head. “What’s the matter, Grandma? Are you chicken?” “You mean I won’t have to listen to all your nonsense anymore?” “And I won’t have to listen to yours either,” said Edith, “except you still get to read me a story every night.” “What if I fall in a hole? Can I holler help?” “No, you have to moo like Albert would if he fell in a hole.” “I still don’t think you can do it,” said Grandma. “Well, we will see about that.” So they tried it. And for a week, they did it. Edith and Grandma communicated with each other like the animals. They stayed close together all day and communicated but did not talk, being silent pretty much all the time, unless they were way out in the meadow and Mother and Dad were nowhere in sight. It worked fine most of the time but not so well in the kitchen or at the dinner table. Mother just didn’t seem to be able to do it. She barely even tried. At the dinner table they would point and nod. Dad just laughed, and he would pass the candlestick or say, “Are you trying to tell me you want some ketchup on your head?” Mother just sat there with her lips tight. During the second week, they were doing great, at least Grandma and Edith thought so, until one time Edith was gesturing for the milk pitcher and she knocked Mother’s water glass over. Mother calmly picked up her water glass and said, “I think I’ve had enough of this grunting and flapping.” “Mother,” said Edith, “we are just doing what Dad does every day. He knows when the cows are hungry, when they need to be milked, which ones need settling down, and he works hard to make them comfortable and he couldn’t do any of that unless he and the cows are communicating, and they don’t have to talk.” “It was bad enough,” said Mother, “when you and your Grandma talked nonsense to each other all day long, but this is worse. Now it’s got to stop, at least at the dinner table.” * * * The August days were lazy and hot. Grandma and Edith spent more and more time in the meadow. Then one aimless afternoon something dreadful happened. They saw a fox catch and kill a mouse in the meadow, right in front of their eyes, just across the creek. He didn’t kill it right away. He did it slowly. He played with it. He tortured it. Now that Edith knew that the mice communicated with each other, and that mice had families, she did not like this at all. She watched the fox take the live mouse by one little leg and shake it like a rag. The leg came off and the body of the mouse went flying and the mouse squealed in agony. And that was not the end of it. The mouse kept flying in the air, still helplessly struggling. Edith stared in horror. Then she shook. Then she sobbed. “Why?” she sobbed. “Why is the fox doing that? Why, Grandma? Why?” “There is no why,” said Grandma, “He just is.” Grandma just could not explain it. Edith lay back down next to Grandma and they lay there in the grass and there was nothing left to say. Edith sobbed and sobbed. She sobbed in her mother’s arms and in her father’s lap. It was the fox’s nature, they said. It was how the fox survived. Hunters kill deer. Farmers kill animals. That’s where meat comes from—chickens, turkeys, and cows. “Cows?” said Edith. * * * One morning Grandma did not get up. She stayed in bed and Mother called Dr. Petrie, who came right away. Grandma had been sick for three days. Mother was in the kitchen preparing a tray for Grandma. Edith noticed that today there was more on the tray than tea—some soup and bread. “Can I go up with you to see her?” “Maybe tomorrow,” said Mother. She looked tired. “Tell her I saw a hawk today,” said Edith. “Why don’t you draw her a picture?” Edith slid her picture under the door of Grandma’s bedroom. Finally, after two more days, she was allowed to see her grandma, who was sitting up in bed and looking just the same as always. “Why didn’t you let me see you?” said Edith. “I was sick.” “You don’t look sick,” said Edith. “I saw a hawk in the meadow.” Grandma raised her eyebrows. “That was the picture I drew.”

“Oh, a hawk,” said Grandma, as she reached for the picture on her nightstand. She studied it—right side up, sideways and upside down. “Hmmm,” she said, moving it close to her face then far away, with her arms out straight. She lay the picture on the blanket in front of her. "Well now, this is quite a picture, Edith. Can you tell me about it?” “Well,” said Edith. “It was circling. Going around and around in the sky, you know, like you and me saw, and then he stopped and dropped, like he changed from a bird to—like a pointed bullet. That's what I drew. These lines here are like speed lines. He is going faster and faster, and his feet are stuck out like this. They were big. This is his feet I drew here, maybe not quite this big. Down here. This is the bunny, except the ears were all I could see, so that’s all I drew.” Edith stopped talking. “I see, yes,” said Grandma, “bird feet, bunny ears, of course.” They looked at each other. “It was sad what happened to the bunny,” said Edith. Grandma did not ask what happened. “But it must have been exciting,” she said. Edith eyes got bigger. She nodded. She knew Grandma would understand. “You should have seen it,” said Edith. “That’s why I drew the picture. I didn’t tell Albert about it or Mother. It would be hard for them to understand. Do you want to play cards? Do you want to go out in the meadow?” “Maybe in a few days.” * * * Finally, Mother said maybe Grandma would get out of bed if Edith would make dinner. Everyone pronounced it delicious, although Edith noticed there was a lot left over. They played cards and Edith lost, then went out into the meadow and lay on a blanket under the stars. “Just for a few minutes,” Mother said. The Milky Way spread across the sky. They lay close together so they could feel each other’s warmth. “Next week, I’ll be in third grade,” said Edith. “Good riddance is what I say. You made me waste my whole summer.” “Will you miss me?” “Not for a second. Albert and I will sit under the apple tree and talk every day,” said Grandma. “Do you think I could teach him to play cards?” “Careful, Grandma, he might beat you.” “I wouldn’t care if he did.” “Liar.” “I’d let him beat me the way I let you beat me.” “Liar. You never, ever, ever did that.” “Well, I tried, but you weren’t smart enough.” “Very funny,” said Edith. It was so quiet the stars got brighter. “Look, Edith, a shooting star. Make a wish.” Edith saw it. She could have wished the summer would never end, but she didn’t. “My meat loaf didn’t come out so good, did it?” she said. “To tell the truth, it tasted like cat food.” “Yup, it did. Mother probably won’t ask me to cook dinner again for a while.” “God, I hope not,” said Grandma and closed her eyes.

|