|

|

|

|

|

|

|

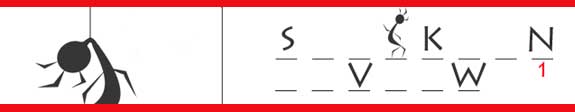

The Sea Gods When I was thirty-four, my father called for the first time in seven to eight, maybe ten years. I can’t be sure; time gets away. I remember it was…I remember I was just out of the hospital, that last miscarriage, just beginning to pretend to heal. My body was ready, but I was not. I had wanted a child then, like yearning. I can admit that now. Years later, I can admit things now. I wanted a child, my child, the last one I lost. And the doctors said I could have her, but they were wrong; my body wouldn’t respond right again; the moon bayed the sun again; something happened intangible and cruel. Anyway, I couldn’t keep her tucked inside me long enough, too soon, gone. The doctors didn’t recommend I try anymore. No more babies, they said, as if I had even one. My father, he called twenty-one days after the death of my child, that girl I never held. I remember the phone call in my kitchen and hearing his gruffness. “Girl, you know who this is?” It occurs to me now that he might have known then about that other hospital stay, my loss of myself like rocks in cans rattling. I hadn’t handled her loss well. Perhaps that’s an understatement. Instead of one large eating area, the Blue Horseman’s Inn had separate rooms where they sat you in gigantic, hard, dark wood seats, polished high. There are no benches or booths in the pictures on the Internet, and all you can see in the pictures are those tables by the sea, soft lit candles, those starched white tablecloths like sails at rest. And the rain coming down. It rains there a lot; I’ve read the reviews about those people who like to look out the latticed windows, look to the pier and rocks outside. The company really got into it with those separate rooms. There was the Triton room, the Poseidon, some room named Nereus, and some other rooms. I could go on but you get the point, you get the joke. I mean, is it just me, or does it seem strange that these gods that people once feared, worshipped even, are etched in gold scroll in wood, over the doorway of each respective room so that someone rich like a Reginald or Baxter the third could have a fine dining experience? I look at Charlie and he looks at me like I am reading too much into it. I do that, read too much into things that have no meaning. My father is standing there under the restaurant’s canopy; rain falls everywhere but on him. I do not wave to him. I admit it now that I should have listened to Charlie when he told me not to name her, but I did. I could not bear it, her not having a name. I named her, Maeve, my mother’s middle name, because I thought the name was beautiful and I wanted a name close to love, history tucked in my heart. Mama, still alive, didn’t want a dead baby her namesake, but she held her tongue and held me, rocking me as she watched now for any sign of further “incidents,” even moving the kitchen knives away from my own kitchen, agreeing to anything I said. “Yes, baby. Yes, baby,” she said. Anything to please me. She was there when my father called. She picked up the phone, looked startled, snapped a few words, and then handed the receiver to me, the cord taut from her hand to mine. My father’s voice, a roast broiling in the oven, the drip of the sink of water not turned completely off. We are moving toward the Blue Horseman Inn’s canopy out of the rain, slowly toward my father. And time has been closer than kind to him. He looks like what I vaguely remember, dark, eyes deeper, body tall, barely bowed. He is wearing a black suit, a little too shiny; a white shirt, a little too crisp. He opens his arms a little like he has practiced it, closes them quickly like he never did. He nods to me. He nods to Charlie, who makes his own introduction. We go inside all strangers. I told Charlie I was all right when he held me after the first “little destruction”—bracing both our weights against the bathroom wall, holding me up, stilling my hand, the water rushing down the sink, the blood. Look away. I know he didn’t believe me then. I don’t think he believes me now. Perhaps he’s right not to. My Charlie, who doesn’t ever mention the little girl we lost; she would have been his baby too, but then Charlie doesn’t mention things that can’t come back: his son’s death to leukemia, that career he drank away, any mistakes that hurt more than him. Charlie looks at life like the sea’s waves doesn’t ask where they are going and doesn’t expect anything back they take. A tall man in a navy blue waist apron and matching tie seats us. Waiters bring us water and menus. The room has pale blue wallpaper above white wainscoting. I look at the polished wood above the doorframe, Nereus etched in gold lettering. I know the goddamned myth about the kind father of the sea and his prophecies. None of which is true here. Still, I look at my father and try to make a smile for propriety’s sake, try to make goodness even if I don’t feel it. My father clears his throat. “Emma Kay, it’s been a long time, yeah, girl?” I don’t look into his face, only his hands on either side of his cutlery, the many veins, the short blunt nails, scarred knuckles. Charlie says nothing, just holds my hand under the table. “Can’t you talk to me, Emma Kay?” my father says, that same voice older now, more graveled, a pleading in it distant from lack of use. They say I asked for my father when in the hospital—when they took my baby from me, only letting me see her eyes-closed face after I screamed for them to, no not that hospital visit, but that “other” stay. They say I didn’t mean Charlie when I called. They say I asked for my father, and somehow he came. They say that I asked for this man who I never remember holding me, never tucking me in at night, no prayers or kisses for me, nothing but broken visitations and promises, and my love scattered like so many sands in the desert. Me, thirty-four, in my pajamas during the day while some man, a doctor in the most awful plaid shirt, blinked at me quickly to gauge my response to reality. Now, I see the craft. Now, I see it. I think the windows really are like the Internet shows, like in the Blue Horseman Inn’s online advertisements. I think the hard, dark wood seats, polished high are there to cradle you, the soft lit candles intimate, the rain coming down like memories at the shore. And I know it’s all fake, planned, made up to make money, but I just can’t see how they count on the rain, how they make it happen. The waiter comes back and backs away, face stoic for our beginning moments. I look at my father’s tie. Now, I remember the name my father called me when I was very little and when I still loved him. I see him holding me, but I know it never happened. I see me holding Maeve in a white blanket; also never happened. I think pain then, because I wanted to hold her, and they wouldn’t let me. And I wonder if somehow my father ever felt that, and it’s raining inside me. Now, I meet my father’s eyes in the Blue Horseman’s Inn, which isn’t an inn but a restaurant, and in the Nereus room named for a god which my father isn’t. Charlie grips my hand tighter, but he still says nothing. The bread comes. Outside, the sky is deepening; tonight there may be a moon. “Emma, Kay…” I want to say something in the lull, in the calm between the waves. All that to say this, I hadn’t handled her loss well, Papa. All that to say this, where were you, Papa? Instead I say, “Yeah,” which I mean to come out like a statement of fact but reaches out like a question as I clear my throat in the Blue Horseman’s Inn. The waiter brings us bread shaped like woven fishes. And my father turns his palms up, hands cupped. He bows his head. His lips move in prayer softly. Neither Charlie nor I bow our heads, but now I can look at my father. All that to say this, my daughter will never come back to me, Charlie will not be with me forever, and maybe my father prays for me just long enough and well enough for the sea gods to hear, the ones brushing against us all forgotten.

|